Leighton: round 2

This time the government try and step into Bristow & Sutor’s soiled shoes…

Last time we brought you the news about the Landmark Leighton judgement here

:

Council Tax debts have now become unenforceable by Bailiffs

The High Court has just handed all Council Tax defendants a potential £4000 Christmas bonus if they sue bailiffs for attempted enforcement which has just been made illegal by a landmark ruling in the case of Leighton versus Bristow and Sutor which showed that the bailiff company didn’t have the correct paperwork when they turned up during an 8 year camp…

Now this case is going to the next level…

Wayne Leighton is going to the High Court to get the outstanding questions that we posed settled. Hats off to him for his tenacity 🦾

Leighton Part 2: what will happen next?…

2 weeks to go before the Wayne Leighton Hearing 13th May 2025:

There are 3 Applications for the court to consider in the case management hearing.

MOJ application to ‘correct’ defendant ( the government are trying a bait and switch manoeuvre to make the government the defendant and not The Court who issued the incomplete previous judgment )

WL application to add Housing Minister and others ( After CIVEA, IRRV and instantly forgettable toothless enforcement quango all DECLINED the government invite to be parties! Quite why Wayne wants these useless eaters and shills to be parties to the action is a mystery, but the fact they declined is interesting 🤔 )

MOJ application for extension of time after failing to respond.( dumbos didn’t respond in time but no doubt the judge will bend over backwards to reward the government for their laxity when mere mortal Litigants in Person would have been ruled against and told off 🧑🏻⚖️🧏🏻♂️ )

The issues of the case are:

A. What is the source of authority for enforcement? We will tell you below … ⤵️

B. What are the limits of Councils authority?

C. Is CTAER1992 compatible with HRA (ECHR) 1998?

THESE WILL NOT BE DISCUSSED AT THE HEARING WHICH IS TO DEAL WITH THE APPLICATIONS BUT HERE IS OUR TAKE ON IT…

This is the garbage that idiots like Mrs Lancaster come out with to try and defend Bristow & Sutor’s position…

You can tell when she says that there is no obligation to show any ID before they show up that she is basically lying, here is what the law says:

“2)The request may be made before the enforcement agent enters the premises”

This was the bit she missed off after she quoted the first bit of the law, sneaky huh? 🧏🏻♂️

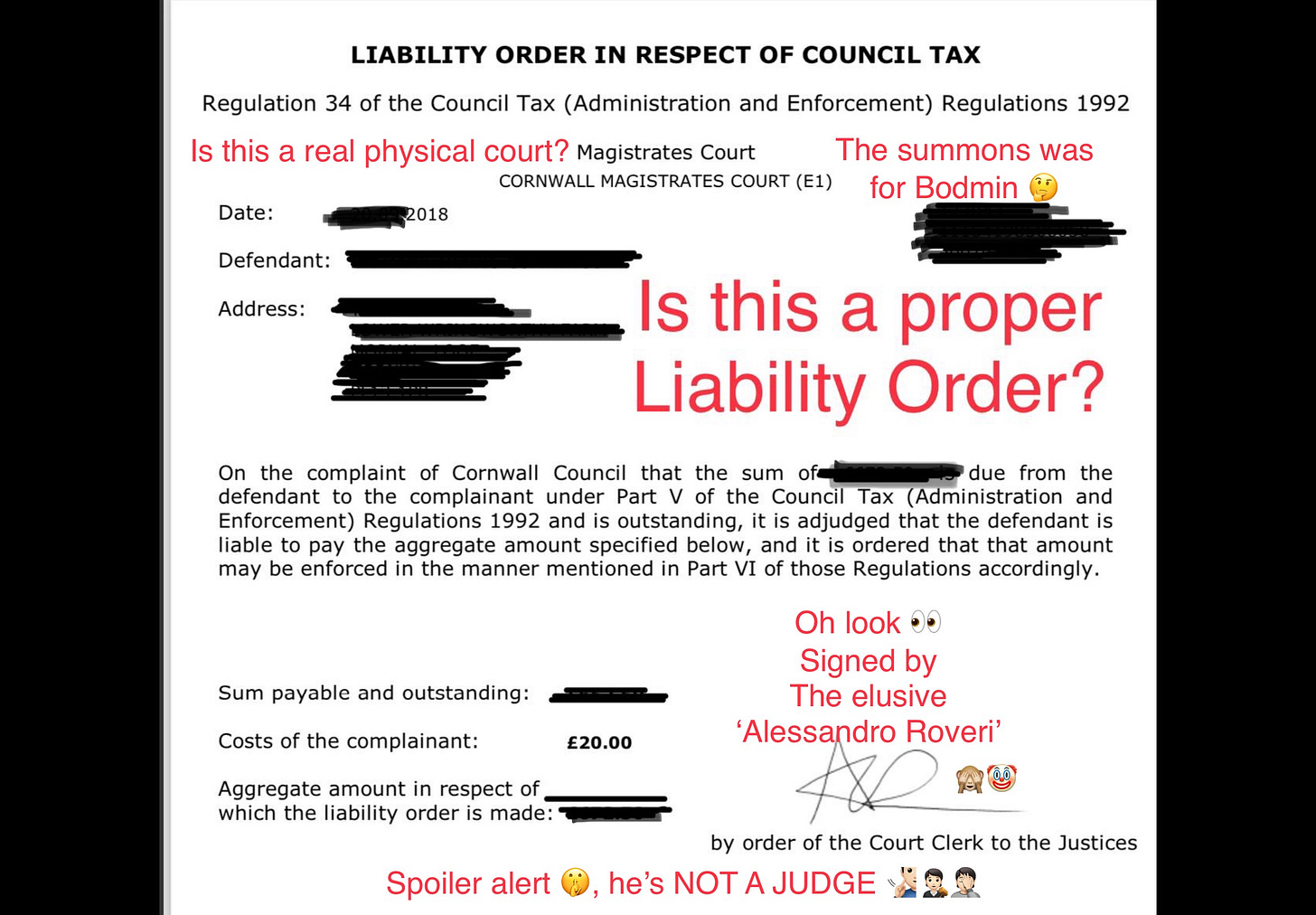

So here is an example of what council’s claim is a ‘Liability Order’

although this is dated 2018 ( before the Leighton judgment ) it was supplied recently in response to a request for a liability order so councils are still pretending this is a real and legally valid order of the court.

So here is what we think is the answer to question A

Let’s see how much of it gets found correct by the Court …

The Leighton Judgment Analysis

This matter involves 6 parties who are all directly related

The Debtor

The Enforcement Agent/Officer ( Bailiff )

The Enforcement Company

The Council

The Court

The Judiciary

The relationship arises initially due to indebtedness from the Debtor to the Council and the Council outsources the collection of the debt to the Enforcement Company who employs the Enforcement Officer as an Agent who is licenced by The Court and supposed to be regulated by The Judiciary via the court who issues the Enforcement Officers Licence which is secured with a £10,000 bond.

The Leighton Judgment impinges upon the final stage and concerns the obligation of the licenced Enforcement Officer to comply with The Tribunals Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 Schedule 12, Section 26 which gives a remedy at Section 66, and the general provisions of The Protection From Harassment Act 1997 and possible remedies at Common Law.

Overview

The Leighton Judgment found ( the ruling stamped 20th September 2023 ) that the Bailiff avoided a charge of harassment as it ruled he was entitled to hold a reasonable belief in good faith that they were acting lawfully by holding an “Authority to Act” document given by The Council to The Enforcement Company who employed the Enforcement Officer and which allegedly evidenced a bona fide reason to breach the peace of the Debtor and also in accordance with the legal requirements ( set out in TCA&E 2007 Schedule 12 §26 ) by presenting their Court issued ID which identified them via an internet searchable database and the same statute ( at section 66 ) also gave the Debtor an avenue of redress via the Issuing Court who held a £10,000 Bond as surety for any transgressions by the Bailiff which could be accessed by an EAC2 complaint to the issuing Court which could result in a hearing of any grievance arising from the conduct of the Bailiff. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/642a8bb37de82b000c313445/EAC2_0414_web_save.pdf

The jurisdiction and process of the EAC2 complaint is however opaque and ill defined from the Debtors point of view and seldom results in action against the Bailiff and requires urgent attention by The Ministry of Justice to redress the imbalance between the parties and to clarify the rights of the Debtor and clarify the process which unfortunately exists in a legal limbo of neither Magistrates’ Court or County Court. In EAC complaints judges frequently either dismiss complaints without reason or find that no wrongdoing has taken place and sometimes hold the hearing in secret so even the avenue for redress is tainted with the same corruption as the offence.

The Leighton Judgment did find in favour of the Debtor Wayne Leighton against the Enforcement Company on the basis that the ironically named ‘Authority to Act’ turned out to be no such thing and was found by the judge to be insufficient proof to a debtor evidencing a right to enter the premises when challenged.

The judgment did not specify what proof was required, but clarified that the Debtor was entitled to be shown evidence from The Court and that evidence from the Council themselves which was in essence self certification and did not evidence any legal authority granted in Law as required in TCA&E section 26.

Since the Leighton Judgement in September 2023 the position of the Enforcement Companies has been severely prejudiced by this ruling which threatened to completely undermine their present lucrative business contracts in terms of the Council Tax debt collection model under which they can obtain £135 for simply posting a letter through the door of a debtor whereby the Leighton ruling introduced additional obligations of direct proof upon them and opened them up to additional remedies under the Harassment Act which threatened the viability of their current business model.

Councils also now faced potential action as an accessory under their vicarious liability along with the Enforcement Companies and they sought to protect themselves with plausible deniability by adding clauses to their now outdated ‘Authority’ Documents imploring the Enforcement Companies to collect on their behalf ‘in accordance with TCA&E’ despite this not being explicitly clarified and hence this shifted the burden from the Council to the Enforcement Company.

This left the Enforcement Company with the thorny problem of compliance which was not explicitly defined in the Leighton Judgment and the fact that since the publication of the Leighton judgment on 20th September 2023 they could no longer rely upon holding a reasonable belief that their enforcement actions were lawful and hence were open to claims of Harassment in addition to breaches of TCA&E. This threatens to completely undermine their business model.

These obstacles would seem to be so inconvenient as to be insurmountable in the circumstances due to the fact that there has been no evidence that any enforcement company has adopted additional processes in order to evidence their authority to act by providing any source documentation from the court. The enforcement agencies ( even Bristow & Sutor themselves ) have instead simply denounced the Leighton judgement in the hope that the general complicity of the system and the lack of inertia by the debtors would nullify any attempts at redress. Consequently this has resulted in them being able to continue their corrupted business model despite the fact they are not strictly operating within the bounds of the law.

If every debtor was aware of the Leighton judgement then council tax debt enforcement via bailiffs would cease overnight! There was a recent example of a video circulated by ‘the Yorkshire lass’ which shows a debtor persistently demanding the court issued proof and the hapless bailiff being reduced to tears when they realised they have been set up as a Patsy by their employer. https://open.substack.com/pub/the98thmonkey/p/yorkshire-lass-successfully-fends?r=zpppo&utm_medium=ios

In the meantime the Ministry of Justice has failed to protect the Bailiffs from this exploitation and more importantly the Lawful rights of vulnerable debtors for a year now and has shamefully postponed issuing any statement or guidance on the matter on the pretext that a pending appeal by Mr Leighton, would prevent any such guidance and therefore delayed and in effect denied justice for the public by their shameful inaction.

Wayne Leighton is due in court for a case management hearing on 13th May 2025 in connection with his case which asks the court to further define his previous ruling.

It should be noted that HHJ Harrison at the end of Paragraph 4 of his judgment aptly describes this whole process as “ripe for reform” in cognisance of his discoveries at how dysfunctional and corrupt this system had become.

The thorny problem of what exactly constitutes lawful evidence remains, and although an ‘Authority to Act’ was ruled to be insufficient there was no indication of what may be sufficient, and the enforcement agencies have seized upon this limbo to interpret the matter to their advantage.

The Enforcement Companies were in the meantime well aware of their obligations and were at one point caught surreptitiously sending observers into Council Tax court hearings as potential witnesses to the granting of bulk orders in order that their witness testimony could potentially be used, but this avenue has yet to be revealed but it would not be direct source evidence and be tainted by the fact that any such witness would not be independent as they would have an inherent vested interest.

The position of the Debt Collection company Rundles typifies the misinformation used by them to perpetuate their business. In essence they claim that they are totally unable to obtain any copy of the required Liability Order on the basis that such a document was not just de-proscribed in 2003 by CTA&E but that this measure “removed any legal requirement for a Liability Order to be produced in document-form” which is an incorrect assumption specifically concocted to give them a plausible excuse to pretend they are unable to act.

They then go on to compound the duplicity by inferring that it is the Council who are the issuers of the Liability Order and directing the Debtor back to Council to ask for a copy of a Document that does not (yet) exist by stating “the Council do not currently issue such.” as if to suggest that it is the council who issue the liability order and not the court.

They then go on to erroneously claim that “the case [and subsequent judgment] was not about producing a copy of the liability order but using the incorrectly worded Authority to Act letter as proof of the enforcement agent’s authority to enter, rather than the enforcement agent’s certificate.” Which is an excuse that is widely used my many enforcement companies which shows collusion in this respect.

Suggesting that as an ‘agency’ who are employing the Bailiff they can in effect derive protection by this self certification in some way ( which is not explained ), by claiming to be standing under their employees certification by saying “the enforcement agent’s authority arises from his/her certification under the 2007 Act [specifically, The Certification of Enforcement Agents Regulations 2014] and it is production of the enforcement agent’s certificate [on demand] that provides the necessary authority for him to enter relevant premises. Accordingly, the case [and subsequent judgment] was not about producing a copy of the liability order but using the incorrectly worded Authority to Act letter as proof of the enforcement agent’s authority to enter, rather than the enforcement agent’s certificate.”

Inferring that the ‘Authority to Act’ could be amended to capture the scope of the Enforcement ‘Agent’ and by referring to the Enforcement Officer now as an “Agent” ( not an Officer or an Employee which they arguably are ), they could then by this convoluted mechanism confer the benefits of the Council’s newly revised Authority to Act directly to the ‘Agent’ which would then obviate the need to prove to the Debtor that there was a genuine Liability Order from the court in their name which needs to show exactly how much they owe.

It should be clear that the Enforcement Company are ‘Agents’ of the Council in law under their ‘Authority to Act’ and that the holders of the Bailiff certificate is in turn their employee in their own right and it is arguable as to whether this certification extends to the Enforcement Company and how it confers any rights directly upon them in turn to benefit from such certification.

In very recent circumstances in an ongoing case to be concluded in 2025, Bristow & Sutor have tried once again to shirk their responsibilities by claiming a defence that they are not the correct defendant in order to evade liability for damages under a case brought on the principles of the Leighton ruling.

If we refer to the Leighton judgement at paragraph 11 we will see that it clearly shows that even an amended authority to act which specifies TCA&E is insufficient by saying” “In accordance with the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, we authorise enforcement agents employed by Bristow and Sutor to enter premises and take control of goods, in connection with debts owed to the City of York Council.”

“As the case has progressed before me, Mr Fender, counsel for the defendant, recognised that this document could not be read as providing authority to the defendant to do what the letter says. Rather, it can only amount to a written confirmation of instructions to the defendants to act on behalf of the council.” This comment is therefore explicit proof that an authority to act is insufficient in itself to grant legal authority when the Enforcement Officer is challenged.

Furthermore at paragraph 25 the judge explicitly denounces any authority for the enforcement officer to benefit directly from the defective authority to act from the council by saying

“The suggestion that the council, as effectively clients, can authorise employees of the defendant to enter premises and take control of goods is problematic, to say the least. Mr Fender characterises the document as an unfortunate piece of drafting, and concedes it could not form the basis for authority for the defendant to enter premises.” Rundles also go on to deflect responsibility and refer the debtor to the council which is specifically prohibited by the judgement in paragraph 27 which says: “it is not, in my judgment, sufficient simply to signpost him to the local authority.”

Leighton Judgement Ratio Unless the enforcement officer is able to produce to the Debtor, when challenged, some sort of primary source documentation evidencing a specific debt in their name then any such claim by the enforcement officer will remain in law to be effectively hearsay if they attempt to evidence their claim by using any statement or document from the council instead of written proof from the court itself which is signed by the justice of the peace making that order in accordance with R vs Sherman Ltd. (1949 )

The obvious remedy for all these problems is for the enforcement officer to provide the debtor with a certified extract from the courts memorandum showing the liability order granted in the debtors name. This could be obtained in any number of ways by the enforcement agent themselves from the court that they are licensed from, or the council or from their employers the enforcement company.

The Issue of actions in good faith evidenced by a ‘reasonable belief’ As early as Paragraph 4, HHJ Harrison clearly sets the scene for his judgement by considering the Mens Rea of the Council in the first instance by saying “the council proceeded to enforce what they saw as a legitimate obligation on the claimant, and one which they felt they were obliged to pursue.”

The basis of Mr Leighton’s case is summed up by HHJ Harrison in Paragraph 9 by saying that “Mr Leighton makes the point that, in the absence of any paper record, then the court should not be satisfied that any such liability order was ever made against him.” Is therefore abundantly clear that this matter turns upon evidencing the so-called “liability order” and this has nothing to do with any purported certification of bailiffs via their ID in an individual capacity as proof of authority. This is further confirmed in paragraph 13 which says “he argues that the defendants have proceeded under a defective instrument, in that no liability orders were in fact made in his case,”

In a recent development case law from 1949 R vs Sherman Ltd. has surfaced which shows that an order of the magistrates court is not active until the justice of the peace signs it by saying: “ we must hold that in the particular circumstances this order was not made by the magistrate before the bill was signed. That being so, when the bill was signed and when, therefore, the indictment became effective there had not been a compliance with s. 3 of the Criminal Justice Act.” Consequently by this reasoning it can be concluded that there is no such thing as a liability order unless and until a justice of the peace signs it.

The judge in Leighton provides a summary in paragraph 19 which shows that in the prevailing circumstances the enforcement agent was entitled to a reasonable belief that what they were doing was lawful: “19. Putting oneself in the defendants’ position, they were being told by a public body that for enforcement purposes, liability orders had been obtained against individuals on a list. For the purposes of paragraph 66(8)(b), that would amount for grounds for a reasonable belief on the part of the enforcement agent that there was in existence a non-defective instrument. It was not, in my judgment, necessary, in order for the enforcement agent to have a reasonable belief, for him to go further and enquire how the order was obtained, or the process involved.” Well, it is now. Consequently now that the Leighton judgement is published law then this reasonable excuse is extinguished and any enforcement officer must be satisfied that their instructions are lawful and ignorance of the law is no excuse.

Despite this being the case, interactions with enforcement officers have revealed that they have no idea of the Leighton judgement and have been kept in ignorance by the enforcement companies who employ them and have continued to use them as hapless patsies to do their bidding with plausible deniability.

In paragraph 12 the judge, HHJ Harrison quotes from section 66 of TCA&E which confirms that the action taken may be specifically grounded on the liability order being defective by omission when it states “(b) order the enforcement agent or any related party to pay damages in respect of loss suffered by the debtor as a result of the breach, or of anything done under the defective instrument.” It can therefore clearly be seen that the ratio of the judgement turns upon the ‘instrument’ (the liability order) and it being held to be “defective” under the meaning of the act and within the precise scope of what the act is attempting to prevent. It can be clearly seen that the alleged liability order is not so much “defective” but entirely absent as it is not an ‘Order’ unless it is signed by the Justice of The Peace that has applied their mind to it and authorised it under their judicial oath by using their conscience.

At paragraph 15 the proof supplied by the council is examined and the judge remarks to the effect that the person making the order should be named in order to evidence the judicial process being carried out by saying, “The documents, as I say, do reveal a series of problems with the process. By way of an example, the name of the individual making the order is not readily discernible.” This means that any court issued proof must carry the name of the judicial officer that made the order and this therefore cannot be a court Clerk or legal advisor.

It is clear that in the Leighton judgement that the judge was not satisfied that there was any proof beyond reasonable doubt that the order had been made and therefore he had to resort to determining the matter merely on a balance of probability despite the fact that in the initial case the court should have been satisfied that the matter was brought by the council and proved beyond reasonable doubt and he had to revert to which version of events he “preferred” which is the weakest and most watered down type of judgement that is not based on any fact that is before the court but that is made merely on the whim of the judge rather than with reasoned fact as it should be.

The crux of the judgement is explained in paragraph 26 in the following way: “In my judgment, a householder is entitled to ask the defendants ( meaning the Enforcement agent ) on what authority they are purporting to enter his property, and the fact that they cannot do so, and refer him back, effectively to their client, is almost bound to cause him to be dissatisfied. In my judgment, the defendants are in breach of paragraph 26.”

Earlier in the judgement it was stated quite explicitly and on numerous occasions that under no circumstances was an “authority to act” capable of complying with section 26 even if it contained retrospectively added references to the act and therefore when challenged the enforcement officer must logically provide something else as proof.

The reference to the debtor being referred back to the council unfortunately does not explicitly mention a liability ordered by name however in the context of the forgoing judgement and taking the evidence of the enforcement company into account then it is clear that this mention is referring to the provision of proof that a liability order has been granted despite the format of this proof not being explicit. The reader is invited to consider if the ‘authority to act’ is not sufficient then what else could possibly be the required proof ?

Therefore it is reasonable to read the judgement as requiring the enforcement officer to show some sort of proof that the liability order has been made and that this is not capable of being supplied by the council because the debtor is entitled to be “satisfied” and due to the fact that it is the council attempting to enforce the debt then it is reasonable for the enforcement officer to show an actual order of the court rather than some biased home-made document by the council. It should be stated that in similar circumstances when enforcement officers are entitled to be on the premises then it is normal custom and practice for them to have and present for scrutiny an original order of the court which is signed by the judicial officer being ‘discernible’ making such a written order as was alluded to in paragraph 15 of the judgement. I.e. it needs to be signed by a judge or magistrate and that judge or magistrate must attach their name also.

In paragraph 44 the ratio for the judgement is further underscored explicitly by stating: “We now know that they felt that the letter from City of York Council was enough to act. As it transpires, it is accepted that the letter cannot amount to the same. I have concluded that, had they stopped to think about it at the time, they should have realised this and perhaps sought to put in place a system that allowed them better to evidence their authority to act. Equally, it seems to me that someone in the claimant’s position is entitled to be told on what authority he is threatened with entry to his premises.” Remembering that the ‘authority to act’ was held to be insufficient.

The whole issue also hinges around collection of a debt which is a ‘sum certain’ that is to say that it is a fixed amount and this fixed amount must be evidenced and this is prescribed as a debt in section 26’s introduction “(4)“Debt” means the sum recoverable.” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/15/schedule/12

Consequently it follows that in order for this ‘sum’ to be recoverable the debtor is entitled to it being evidenced in some way and this evidence of the actual sum of the debt is in addition to the evidence of the authority to enter the premises or else the act would not specify the debt as a specific sum recoverable in a separate clause.

With regards to distressing goods to the value of the debt then this also must be a consideration in order that the enforcement officer can act reasonably and proportionally in distressing the correct goods, otherwise, how does the Enforcement Officer know the value of goods that he is authorised to take? because any authority to enter the premises is only to take goods equivalent to the relevant "sum". The authority to enter the premises is not just the authority to enter, it's authority to enter AND take goods to the value of £x - and so the authority to enter relied upon needs to demonstrate the value of x to demonstrate what the authority is (extents and limits), and this needs to be provided to the debtor on request. Otherwise it is impossible to know when he exceeds his authority.

The authority to act is also non-specific and very general in its scope and the Authority to Act letter from the local council to the Enforcement Company does not have any personal information on it which proves the debt is specific the the debtor ( but more recent versions have attempted to insert a catch-all clause to this effect to plug the loophole) and the Enforcement Agent should provide proof of the transfer of authority by evidencing the proof as opposed to a verbal claim.

Harassment The judgement rules that the requirements for the Harassment Act were not triggered because at the time the enforcement company has a reasonable belief that they were acting lawfully and in accordance with the unfortunate nature of their job, however since the Leighton judgement the scope of acting within the bounds of their obligations under TCA&E have been clarified and a definition of a breach of section 26 has been established and therefore any circumstances that mimic those of the Leighton judgement by failing to provide evidence of the authority to act as Bristow and Sutor failed to do may bring any such transgression within the scope of a breach of the Prevention from Harassment Act 1997 which is summed up as: “their persistence in continuing with a process against a background of what I have concluded was a breach of the Schedule on their part.” Meaning Schedule 26 of TCA&E 2007

Remedy to the Problem of proof of Authority The Leighton case clearly defined that the ironically named Authority to Act issued by the Council was not capable of being sufficient in any form and therefore an alternative is required.

Although the issuance of a Liability Order Form A was de-proscribed it does not prevent the Court from issuing a Liability Order and this could be one remedy that would evidence the Liability Order from the reliable third party source.

It should be noted that the original legislation specifically uses the word “ make” and therefore one must consider what the intention of parliament was by also looking at the fact that it proscribes specifically formatted documents as written evidence that the order was made. Therefore a reasonable conclusion can be drawn that it was definitely the intention of Parliament that a liability order must be evidenced in writing and that a chain of hearsay evidence is not sufficient.

The Enforcement Company or Enforcement Agent/Officer could also obtain a Certified copy of the Memorandum of Entry from the Court record in accordance with the section 66 provisions of the Magistrates’ Court ( Amendments ) Act 2020 and would be required to pay the required fee.

The council issued “Notification” of a Liability Order is also insufficient in law because it is a home-made document doesn’t come from a verified third-party and is therefore similar to the now unlawful “authority to act”.

What is logically required is the original authority that comes from the actual Liability Order itself and not from the council who cannot hold any actual legal authority.

The council are in effect simply a biased third-party attempting to pass off their own hearsay as primary evidence in order to obtain money.

The role of the judiciary The judiciary play an important part in ensuring that the enforcement officers are regulated and licensed to act lawfully and should act to ensure that the proper procedures are followed and that the law is observed.

The courts are responsible for licensing the bailiffs and consequently must take steps to ensure that the appropriate avenues for lawful compliance with statute and the case law of the Leighton ruling is available to the bailiffs to ensure that they can easily adopt the appropriate procedure and not deviate into unlawful practices which are the easy option that is unfortunately driven by the financial interests of the enforcement agencies.

The mechanism of redress is by an EAC2 form sent to the court to complain about the bailiff, however this process is opaque and has no discernible procedure and judges such as Judge Suki Waschorn and others are seemingly ignorant of the law and habitually rule in favour of the bailiffs without providing any reasoned judgement.

The bailiffs must also be protected by the court from being unwitting participants in unlawfully distressing goods at the behest of the enforcement companies who are unlikely to suffer any consequences for the breach of laws in this regard and these agents have in effect been used as hapless patsies by the unscrupulous debt collection companies who can maintain an arms length position of plausible deniability when commenting on the unlawful acts of those whom they employ.

This whole house of cards however comes tumbling down when the debt collection companies are forced to be held to the same standard to which they hold their victims insofar as ignorance of the law is no excuse and in many cases they employ a position of wilful ignorance of the Leighton judgement in order to keep their businesses solvent because if they were to strictly adhere to the letter of the law they may ironically face losing their business which have in effect being hobbled by the Leighton judgement.

In respect of council tax enforcement the enforcement agency model is now a zombie business waiting for the first card to be pulled from their precarious house of cards.

This is obviously not legal advice so please consult a qualified lawyer before taking action which takes into account your particular circumstances.

Any images are used for educational purposes and public discourse.

Thank you!

Not providing sections in legislation to get the upper hand. Lying and conniving BS that are B&S.